Because You Can’t Take It With You…Estate Planning!

The term “estate” is commonly defined as a vast piece of property owned by a prominent family. As in, William Pumpernickel of the Pensicola Pumpernickels invites you to his country estate for croquet and crumpets.

For purposes of this post, I’ll be referring to an alternate definition of estate: an individual’s total assets (e.g., all land and real estate, possessions, financial securities, cash, insurance, and other entitlements). It also includes any liabilities (e.g., mortgage, car loans, and other debt). In other words, an estate is everything that makes up a person’s net worth.

Estate planning refers to management of those assets and liabilities, typically by creating a will, but it’s more than just making a will. So much more, in fact, that I broke it down into two posts. Perhaps we may all be feeling our mortality a bit keener in these times, but estate planning is about more than just morbid contemplation. In fact, it can be fun. Alright, that’s a lie. It’s really not that fun, but it is definitely a responsible thing to do.

In this post, Part 1, I cover who needs an estate plan, probate, estate/inheritance taxes, and components of an estate plan. For a teaser on the contents of Part 2, you will have to read to the end of this post.

Estate planning refers to more than the management of how assets will be transferred to beneficiaries when an individual dies.

Who needs an estate plan?

You may assume that if you have a negative net worth (as is the case with many newly graduated radiologists who carry, on average, $200,000 in student loan debt), that you don’t have to worry about having a will or other estate planning documents. But estate planning refers to more than the management of how assets will be transferred to beneficiaries when an individual dies. If you have any minor children you need to clarify how they will be provided for if something happens to you. Having an estate plan can also minimize the assets that go through the probate process, potentially reduce estate taxes, and clarify who will make medical and financial decisions on your behalf if you become temporarily or permanently incapacitated.

What is probate?

Before getting to the components of estate planning, it’s necessary to talk about probate, because this is something most of you will want to avoid. Probate is a legal process, controlled by a court, that takes place after someone dies. It includes proving in court that a deceased person’s will is valid, identifying and inventorying the deceased person’s property, and distributing the property as the will (or state law, if there’s no will) directs. Probate also ensures that the debts of the decedent are all paid before any assets are passed on to heirs.

There are many negative aspects of probate:

- It can be a lengthy process, in some cases lasting more than a year.

- It can put pressure on real estate sales, leading to accepting a low sale price out of expediency in order to complete the probate process.

- It can be associated with substantial fees, in some cases exceeding 3-5% of the value of the estate.

- Most people don’t have the time or expertise to properly do all of the probate tasks required – there are forms that must be filled out and filed with the court, information that needs to be sent to all interested parties by mail, and there is a need for some accounting skills.

For some, the biggest disadvantage of probate is the lack of privacy. In a probate case, all assets, debts and gifts of the deceased person are reported to the court and become public records. Anyone can go to the court and ask to see what has been inherited by a beneficiary down to the penny. Predators of recent inheritors take advantage of this.

There are two ways to avoid probate: 1) naming specific beneficiaries, and 2) using a revocable trust. Keep reading to learn more about each.

Two certainties in life – death and taxes

And in some cases, they are combined! It’s important to understand tax consequences as you consider how you want to structure your estate documents and manage your assets while you are alive.

“Death taxes” is an unfortunate term that refers to estate and inheritance taxes imposed by the federal and/or state government on someone’s estate upon their death. Estate taxes are paid by the estate and based on the estate’s overall value, while inheritance taxes are paid by an individual heir on whatever property they inherit. Most radiologists won’t have to worry about either (at least at the federal level), but you definitely want to confirm this if you are exceptionally wealthy. If your 2020 net worth is less than $11,580,000 ($23,160,000 if married), your estate will not be subject to federal estate tax. These exemption amounts are indexed to inflation.

Note that the exemption hasn’t always been so generous. It was only $1,500,000 in 2005, $5,000,000 in 2011, and jumped to $11,180,000 in 2018. It’s possible that at some time in the future, the exemption will decrease.

Also note that many states assess their own estate and/or inheritance taxes, often with far lower exemption amounts, in some cases less than $1,000,000. Here are the jurisdictions that have estate taxes, with the threshold minimums at which they apply shown in parentheses:

- Connecticut ($3,600,000)

- District of Columbia ($5,600,000)

- Hawaii ($5,500,000)

- Illinois ($4,000,000)

- Maine ($5,600,000)

- Massachusetts ($1,000,000)

- Maryland ($5,000,000)

- New York ($5,000,000)

- Oregon ($1,000,000)

- Minnesota ($2,700,000)

- Rhode Island ($1,561,719)

- Vermont ($2,750,000)

- Washington State ($2,193,000).

The primary strategy used to reduce that tax burden is to give assets away before death. You can donate any amount to charity and you and your spouse can each give up to $15,000 per year to anyone you like without using up any of the estate tax exemption.

Another less commonly used strategy is to place assets into an irrevocable trust, removing any future appreciation from your estate and lowering or even eliminating the amount of estate taxes that would be due if you were to pass on the assets at death. Keep in mind that an irrevocable trust, by definition, cannot be repealed or annulled.

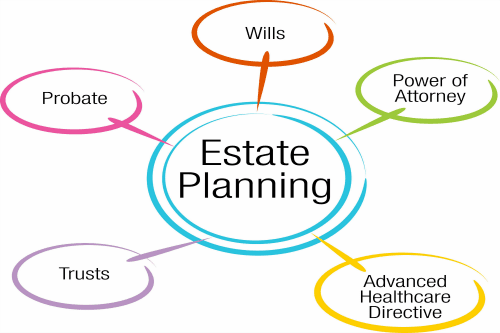

Components of an estate plan

To many people, estate planning means making a will. Although a will is a very important part of an estate plan, it’s only one document among many, and for some, not even the most important.

Wills

A will is a legal document that outlines the distribution of your property and the care of any minor children. If you have children from a prior marriage, even if they are adults, your will can dictate the assets they receive. If you die without a will (aka, “intestate”), those wishes may not be followed and leaves decisions about your estate in the hands of judges or state officials.

Note: Naming beneficiaries, designating accounts as “payable on death” or “transfer on death”, and designating property as “joint tenancy with rights of survivorship” are ways of avoiding probate.

Many of your assets are NOT covered by wills. For example, payouts from life-insurance policies, money remaining in annuities, and retirement plan assets go to designated beneficiaries. The same applies for “payable on death” bank accounts and any investment accounts that are designated as “transfer on death.” Lastly, it also includes property that has “joint tenancy with rights of survivorship” (i.e., two or more owners hold title to an asset together, such as a house; if one owner dies, the asset goes directly to the surviving owner).

Note: Naming beneficiaries, designating accounts as “payable on death” or “transfer on death”, and designating property as “joint tenancy with rights of survivorship” are ways of avoiding probate.

Also note: If a will leaves less to a spouse than state law requires, that part of the document may be overridden, and the spouse awarded the mandated amount.

There are several kinds of wills:

Testamentary wills, the most familiar and arguably the best type of will, is prepared by the person whose assets are being dispersed, who then signs the document in the presence of witnesses. This type of will is the best insurance against successful challenges to your wishes by family or business associates after you die.

Holographic wills are written, signed by the testator (person making the will), but not witnessed. Holographic wills (from the word holograph, meaning a document hand-written by its author) are often used when time is short and witnesses are unavailable. They are not recognized in all states, but even where they are, the absence of witnesses often leads to challenges to the will’s validity.

Oral wills, as the name implies, are oral only. The testator speaks his or her wishes before witnesses. Oral wills are not widely recognized from a legal perspective.

Pour-over wills are used in conjunction with trusts (see below).

A Living will – also known as an advance directive – is different from other types of wills used for passing on property and other assets. A living will is a legal document that specifies the type of medical care that you do or do not want in the event that you are unable to communicate your wishes.

A living will addresses many of the medical procedures common in life-threatening situations, such as resuscitation via electric shock, ventilation, and dialysis. You can choose to allow some of these procedures or none of them. You can also indicate whether you wish to donate organs and tissues after death. Note that refusing life-sustaining care doesn’t preclude receiving pain medication throughout your final hours. Most states also allow the living will to cover situations where you have no brain activity or where doctors expect you to remain unconscious for the rest of your life, even if you don’t have a terminal illness or life-threatening injury. Because these situations can occur to any person at any age, it’s a good idea for all adults to have a living will.

A probate court usually requires access to your original will before it can process your estate. It’s important, then, to keep the document where it is safe and yet accessible. A waterproof and fireproof safe in your house is a good choice. Let your executor know where the original will is stored, along with such information as the password for the safe. Note that if you store your will in a bank safety deposit box, your family may need a court order in order to gain access.

Trusts

In simple terms, a trust is a relationship where property is held by one party for the benefit of another party. A trust is created by the owner, also called a “settlor”, “trustor” or “grantor” (typically an individual or married couple) who transfers property to a trustee. The trustee holds that property for the trust’s beneficiaries. Often, the trustor is the same person as the trustee.

Trusts are particularly useful tools to provide for a beneficiary who is underage. Once the beneficiary is deemed capable of managing their assets, they receive possession of the trust.

A trust is private while a will is made public after a person dies. A revocable trust, where the trust creator has the power to revoke or amend the trust, is the most commonly used type of trust. Much like a corporation, a revocable trust is a legal entity that can own property. Owning and controlling property is the main purpose of a trust. When all of a person’s assets are owned by a trust, the person technically owns nothing. This is how probate is avoided using trusts.

Trusts are not just for the wealthy, but rather a vehicle to control the person’s assets and to make things easy on the person’s family. Trusts do not require a lot of ongoing effort. The only time a trust requires attention is when buying real estate, a vehicle, or opening a bank or investment account, and even then, the attention it requires is minimal and need not involve an attorney. In a revocable living trust, the person who set it up has complete control to make any trades or any sales or use their property in any way, without oversight. There should not be any ongoing costs with a revocable trust (i.e., there is no cost for someone to administer the trust).

Even if you have a revocable trust, you still need what’s known as a pour-over will. In addition to letting you name a guardian for your children, a pour-over will ensures that all the assets you intended to put into the trust are put there, even if you fail to retitle some of them before your death.

Irrevocable trusts are not as commonly used because they are less flexible and difficult to change (i.e., irrevocable). The trustors are not able to use the trust assets for whatever purpose they want. The restrictions are designed to result in protection from lawsuits, bankruptcy recovery, nursing cost spend-down and recovery and splitting in a divorce judgement – all depending on the wording of the trust and the actions and identity of the trustee/s.

Durable Power of Attorney

A durable power of attorney (POA), sometimes referred to a financial power of attorney, is someone that you choose to act on your behalf financially when you are unable to do so yourself. Without a POA, a court will decide what happens to your assets if you are found to be mentally incompetent.

A POA can make real estate and financial transactions, as well as make other legal decisions as if she were you. She can deal with retirement plans, write checks, open and close bank accounts, buy or sell a house, etc., depending on the language of the document. This type of POA is revocable, typically when you become physically able, or mentally competent, or upon death.

In many families, it makes sense for spouses to set up reciprocal powers of attorney. However, in some cases, it might make more sense to have another family member, friend, or a trusted advisor who is more financially savvy act as the agent.

Healthcare Power of Attorney

A healthcare power of attorney (HCPA) is typically a spouse or family member who has agreed to step in and make important healthcare decisions on your behalf in the event of incapacity. You should pick someone you trust, who is aware of and comfortable acting on your wishes, and will recommend a course of action you would agree with. This person may be asked to deal with such things as admission into nursing homes or other residential facilities, when to make decisions about withholding treatments, and how to deal with pain medications, feeding tubes or even autopsies. Given the importance of POAs and HCPAs, backups should be identified.

Beneficiary Designations

As noted above, many possessions (e.g., retirement accounts and insurance plans) can pass to your heirs without being dictated in the will. This is why it is important to maintain a beneficiary (and a contingent beneficiary) on all such accounts. When no beneficiary is named, the court can decide how the funds are distributed. Depending upon your state’s laws, you may also be able to use a “pay on death” or a “transfer on death” designation for bank accounts, investment accounts, vehicles, or real estate. Note: Named beneficiaries should be over the age of 21 and mentally competent.

You may not want one or more of your relatives to raise your children, particularly if they don’t share your views, aren’t financially sound, and aren’t genuinely willing to raise children.

Guardianship Designations

While many wills or trusts incorporate this clause, some don’t. If you have minor children or are considering having kids, picking a guardian is incredibly important. If such a designation is not in place and the custodial parents both die, a court will decide who will be the legal guardian. This will most often be a relative who is willing to take on the responsibility, but in extreme cases, the court could mandate that your children become wards of the state.

You may not want one or more of your relatives to raise your children, particularly if they don’t share your views, aren’t financially sound, and aren’t genuinely willing to raise children. In addition to choosing a guardian, you need to designate someone to manage the assets you leave behind to care for your children. This may or may not be the same person as the guardian – the people with the best parenting skills aren’t necessarily the most financially literate or able to manage money well. As with all designations, a backup or contingent guardian should be named as well.

Wrap-up

That was a quick overview of estate plan documents. But estate “planning” requires (duh) “planning.” Before you get started with that I urge you to read my next blog post, where I will review the role of an executor, when you should develop an estate plan, how much it should cost, and what you can do to limit that cost by being prepared before meeting with an estate attorney. Oh–and also a touch of my personal experience. And for the obligatory Monty Python reference: “I’m not dead yet!”