How to Manage Your Green to Stay Golden (with a Sound Retirement Spending Plan)

“I want the last cheque I write to bounce.”

Chuck Feeney

Ah, the golden years—riding into that retirement sunset. For some, it’s an eagerly-anticipated time in life, filled with big dreams; possibly, plans of moving to Florida. For others, shudder-the-thought. Wherever your feelings might fall on the spectrum, one thing may hold true: you probably don’t want to burn through your retirement savings too quickly.

Yet, indeed, the future is shrouded in so much uncertainty. So what can you do to better ensure your ability to stay comfortably solvent until the end? That is the subject of the day.

In two words: retirement spending.

In more words: how and when you should tap that. And by “that,” I mean, your retirement savings, of course. The nest egg. The well. The coffers. Pick your favorite verbiage—the point is I’m going to offer some very sound suggestions.

The topic of this post may seem most relevant to retired, or soon to be retired radiologists. However, I’m a believer in the adage “if you don’t know where you’re going, you won’t know where you are when you get there.” If you have an idea of what’s ahead in retirement, whether that’s 5 or 25 years down the road, you can plan accordingly.

It’s worth saying up front that there is no “one size fits all” when it comes to retirement spending. First of all, not every radiologist will want to retire. I’ve known plenty of radiologists working into their late 80’s (albeit many part-time) who had no desire to ever stop working. On the other end of the spectrum are radiologists who decide at a relatively young age that they want to retire early. Many of them pursue the FIRE lifestyle movement (Financial Independence, Retire Early). Planning for 50 years of retirement will be different than planning for 30.

A common and important question I hear is “How much of my portfolio can I spend each year in retirement without running out of money?” The answer to this is complicated. In order to come up with an exact amount, you’d need some information, some of which is knowable and some not.

Knowable

- Current value of your portfolio

- Amounts of your pension and any other fixed sources of income

Unknowable

- Your date of death (do you really want to know?)

- Your portfolio returns every year leading up to your death

- Your federal, state, and local tax rates each year until you die

- Future inflation rates

- Future health care costs

- Future value of any real estate you may own

Did you notice that the list of unknowables is a lot longer than that of the knowables? Time to dust off that crystal ball!

Since every individual has their own idea of when and how to retire, and there are so many unknowables, there isn’t one simple recipe that will work for everyone. However, there are some basic guidelines that everyone can follow. But first, I want to share my philosophy on managing finances during retirement.

Flexibility is the key to stability

I was retired for about 4 years and then rejoined the work force because I had the opportunity to do what I loved, with flexible hours, from home. But I continue to follow the same principles I did when I was retired.

The most important of those is to position myself to be able to withstand bear markets, sky high inflation, surprise decreases in pension or social security, marked increases in tax rates or health care costs, or anything else that might substantially change my income or expenses. I can’t prepare for an apocalypse, but there are many things I can control for. I do this by keeping my fixed costs low, maintaining a healthy emergency fund, and eliminating debt.

Fixed expenses cost the same amount each month. They are not easily changed but are easier to plan for. Typical household fixed expenses are student loan payments, utilities/water, mortgage or rent, property tax, homeowners association fees, and insurance premiums. While you could theoretically change your monthly mortgage payment by moving to a less expensive home, refinancing your loan, or by appealing your property tax assessment, this takes some effort. The same is true if you pay rent. You could change this expense by moving to a cheaper apartment/house or by getting a roommate, but these are major lifestyle changes. Insurance (e.g., health,disability, car, life, homeowner’s, umbrella, etc.) is another fixed cost, in that it generally does not change during the year unless you actively research alternate plans to do so. Note: If you are financially independent when you retire, you won’t need life or disability insurance.

In spite of its name, “fixed” expenses are not necessarily set in stone. If you had to, with effort they could be decreased. They typically represent the biggest chunk of your budget, thus any money saved by decreasing them can be quite substantial. Think about how property tax varies by home value. If a $500,000 home costs you $12,000/year in property tax, a $3,000,000 home might cost you over $70,000/year. That’s a $70,000+ expense you have to pay whether the economy is soaring or in the dumper.

Variable expenses, on the other hand, may change daily or from month to month. Examples include costs from eating at restaurants, buying clothes, or drinking Starbucks coffee. Some may change monthly or annually, such as cellular phone and internet plans, or subscribing to streaming services like Netflix. Other variable expenses include household maintenance, vacations, and charitable contributions. Not everyone will agree on what is fixed and what is variable when it comes to things like paying someone else to do your taxes, manage your finances, mow your lawn, or shovel your snow. If you’re unable to do it yourself, you’re probably going to have to pay someone to.

Some variable costs, such as groceries and transportation costs, are not discretionary but can be easily adjusted. You have to eat, but you can choose to price shop, clip coupons, and cook at home. If you have to commute to work, you can drive a gas guzzling Hummer, an eco-friendly Prius, ride a bicycle, carpool, or maybe even walk.

If you keep fixed expenses low, you will be in a better position to vary your expenses if you need to.

The greater your net worth, the more flexibility you will have regarding expenses. Some people become so good at saving and investing that they become “underspenders” and deprive themselves and those closest to them of goods, services, and experiences that can make for a better, happier and more fulfilling life. I don’t advocate that. But the bottom line is that if you keep fixed expenses low, you will be in a better position to vary your expenses if you need to. In a year when the market is up, you can buy that fancy new car. When the market is down, maybe you take the grandkids to Disneyland instead of taking a 3-month cruise around the world. And by the way, spending flexibility can be advantageous in all stages of life, not just retirement.

Tapping the well (or insert favorite money-bags metaphor here)

So, how do you determine how much you can withdraw from the well (i.e, your nest egg) each year during retirement without running out of money? Investment scholars and researchers have used life expectancy tables and historical financial data to come up with viable answers.

At one time, the general consensus was that if your portfolio averaged a return of 8-10% a year, you could spend 8-10% a year. Make sense to you? The problem with that is what is called Sequence of Returns (SOR) risk. That is, the risk that even if you average 8% returns over the course of your retirement, the combination of portfolio withdrawals during a time of bad returns early in retirement will cause you to run out of money early. Thus, the amount you can safely take out each year must be low enough to account for SOR risk.

The 4% Rule

The Four % Rule, created using historical data on stock and bond returns over a 50-year period, states that you can withdraw 4% of your portfolio each year in retirement. It also allows for annual increases to match inflation. Even during untenable markets, no historical case exists in which a four percent annual withdrawal exhausted a retirement portfolio in less than 33 years. In fact, some scholars believe the 4% Rule is too conservative and that a 4% withdrawal rate is too low relative to the long-term historical average return of almost 8% on a balanced (60/40) portfolio.

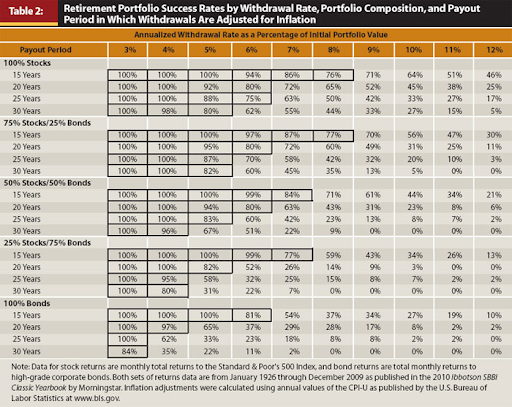

Keep in mind that the 4% Rule assumes a “typical” retirement portfolio that includes 50% in stocks and 50% in bonds. This type of asset allocation allows for a retiree’s portfolio to continue to grow (with stocks) while maintaining a reasonable level of risk (with bonds). A severe or protracted market downturn can erode the value of a higher-risk investment portfolio (i.e., one with a high percentage of stocks) much faster than a typical retirement portfolio. The table below, from the Trinity study, shows the odds of portfolio success by withdrawal rate and portfolio composition. You can see from this table that as you start to withdraw more than 4% per year, or invest too heavily in bonds, the odds of outliving your portfolio go up dramatically.

Further, the 4% Rule does not work unless you remain loyal to it year in and year out. Violating the rule one year to splurge on a major purchase can have severe consequences down the road if it too greatly reduces your portfolio’s principal, which directly impacts the compound interest that you depend on for sustainability.

In addition, the 4% Rule can fail if you have a longer than “typical” duration of retirement, either because you start early (FIRE) or live longer than average. The average life expectancy in the United States is 78.9 years. A 65-year-old man has about one in five odds of living to age 90 and a 65-year-old woman has almost one in three odds of living to age 90. A 65-year-old couple has a 45 percent chance — almost 50-50 — that one of them will survive to age 90. You probably wouldn’t be happy if you were following a plan meant to last until age 80 and at age 90 find yourself eating cat food and living in your grandson’s dank basement.

Do you see now why there is no “one size fits all” answer to the question of successful retirement withdrawal? There are literally millions of safe withdrawal rates, depending on the variables you include in the calculation. A simple answer is that if you start out with a big enough portfolio or guaranteed income (based on the number of predicted years of retirement), you can make inflation-adjusted withdrawals, starting at 4% of your portfolio’s beginning value. Alternatively, you can withdraw a fixed 5% a year. Your portfolio will go up in some years and down in others, so if you take a fixed percentage, you will take a pay cut when the portfolio is down and a pay raise when the portfolio is up.

I’ve not talked at all in this post about how much income you need in retirement. That number will depend on your annual expenses (which will be a guestimate and change over time) and the number of retirement years. The 4% Rule only provides a reasonably safe withdrawal rate. Using this rule, if you want to live on $100,000 a year, you need a portfolio of $2,500,000. If you want to live on $200,000 a year, you need a portfolio that is twice that amount. Keep in mind, too, that some of that portfolio may be taxable. Money taken out of a non-Roth IRA, 401k, or 403b, for example, will be taxed at your ordinary income tax rate.

I have multiple retirement and taxable accounts – what do I tap first?

The answer to this question is also not one size fits all. The most important consideration is to make withdrawals in the most tax-efficient way while also making any required minimum distributions. You may want to spend down funds from any investment portfolio that isn’t part of a qualified retirement plan. Tapping these accounts, which are taxed at a capital gains tax rate, will generally reduce your total tax liability, compared with withdrawing funds from a retirement account, which will be taxed at your ordinary income tax rate.

You can start withdrawing funds from a retirement account without penalty after age 59 ½, but you MUST start taking required minimum distributions (RMDs) from tax-deferred retirement accounts at age 72 (or age 70 ½ if you reach 70 ½ before January 1, 2020). Failure to take RMDs on time results in a 50% tax penalty on the amount of money required to be withdrawn. Delaying withdrawals from these accounts allows them to continue to grow tax-free.

A Roth IRA works differently. There are no RMDs, so you can let that money grow tax-free for as long as you like. Because it’s tax-free, you may want to take part of the money you need for living expenses from a Roth account to achieve a low income tax bracket. If you’re in a situation where you can live off social security, pensions, annuities, investment income, and continued earned income (either your own or that of a spouse), you can limit withdrawals to RMDs from non-Roth accounts. Keep in mind that you don’t have to spend those RMDs. They can be reinvested (in taxable accounts, for example, but not in retirement accounts).

All of us have individual goals for retirement, including what we want to leave behind when we’re gone. Whether you want to shower your heirs with assets or let your last check bounce, you can devise a plan to make that happen. The size of portfolio or income you will need will depend on your goals. The key to making your money last in retirement is to be financially flexible, particularly in the early years, by keeping your fixed expenses low. The definition of “low” will depend on the resources available to you that can buoy you up in times of economic instability. It also helps to follow a sound withdrawal plan, making adjustments when your portfolio is substantially up or down to avoid under- or overspending.

Finally, I hope your golden years are just that.

Doc Collins, signing off.