Interpreting Your Financial Brain: Behavioral Finance for Radiologists

This is a scan of your financial brain. As you interpret the images, you may not initially spot any abnormal findings, but a closer read will reveal the influence of subconscious biases.

In this post, I’ll be diagnosing patterns of thought and behavior that too commonly lead to unsound financial decisions and investing mistakes. Don’t let your psyche sabotage your efforts and hard-earned money. After further examination (aka reading this blog post), a clearer picture will emerge.

Behavioral Finance Mimics Radiology Practice

Behavioral finance, a subfield of behavioral economics, proposes that psychological influences and biases affect the financial behaviors of investors. Individuals are often not aware of these influences. This creates an educational opportunity, and I’m not one to pass up a chance to use my MEd.

There’s a lot of great information available about the psychology of investing, and some of the best of it comes from Jonathan Clements, whose financial website includes a “Human” section. In it he outlines 22 “mental mistakes” made by homo economicus (i.e., the figurative human being characterized by the infinite ability to make rational decisions).

It occurred to me, as I was reading Jonathan’s take on mental mistakes, that many were analogous to the practice of radiology. I thought, “what better way to teach finance than to relate it to a radiologist’s everyday work?” So here is my interpretation of how behavioral finance and radiology practice intersect.

The “mistakes” listed below are described in terms of their financial impact, and some, when I could come up with good examples, are related to the practice of radiology. To make it even more interesting, I also offer up some personal experience.

Consider these 22 misleading perceptions that lead to financial blunders—in “rad-speak”:

1. We’re too focused on the short-term.

Experts advise us to save and invest. Yet, we want to spend money now. By not saving, we risk having to work longer than we’d like or sacrificing our retirement lifestyle.

After 14 years of undergraduate college, medical school, residency, and fellowship, radiologists have gotten used to delayed gratification. They should have no trouble delaying spending for a few years after training to pay off loans before substantially increasing their lifestyle.

2. We lack self-control.

Our ancestors didn’t have to worry about restraining their consumption in order to amass money for retirement. Today, we are constantly bombarded with advertisements intended to get us to buy something now, now, now. Newly minted radiologists, fresh out of training and finally earning the “big bucks”, are eager to buy the doctor house, and the doctor car, and take the doctor vacation. They have plenty of role models to suggest that this kind of immediate spending is “normal.” They may be pressured by a spouse, who has also had to delay the “phase of acquisition.”

That ability to delay gratification continues to be important throughout a radiologist’s career. Promotions take years. Sometimes it takes years to get a paper accepted. Partnerships take, on average, 2-3 years to happen. And in some years, salaries don’t go up, and may go down.

3. We believe the secret to investment success is hard work.

Hard work means actively putting in a lot of time and effort to accomplish a goal or goals. But when it comes to investing, the best approach is often one that doesn’t take a lot of time. Actively reading financial reports and day-trading might render an illusion of control over one’s investment results, but it is more likely to hinder investment performance by racking up costs and making bad investment bets. Smart investing doesn’t have to take a lot of time or daily monitoring.

What does success mean to a radiologist? Is it working 80-hours a week, generating above-average RVUs, and making $800,000 a year? You’d surely have to work hard to do that. Is it publishing 20 papers a year and getting promoted from assistant to full professor in less than 10 years? Where does it end? I don’t want to be the pot calling the kettle black, as I’ve been professionally driven my whole adult life. But newer generation radiologists are looking for more flexibility in the workplace and a healthy work-life balance, and success isn’t necessarily measured in dollars.

4. We think the future is predictable.

In retrospect, it seems obvious that technology stocks were going to crash and burn after the dotcom bubble of the late 1990’s, or that the housing bubble of the early 2000’s would burst. Did we really foresee both market collapses? Or have we forgotten about all the uncertainty that existed at the time? This is a phenomenon known as “hindsight bias.” Thanks to our sanitized recollection of the past, we feel future events are more predictable than they really are and this leads us to make investment decisions that we later regret.

In radiology, the use of hindsight bias is a commonly used strategy in a court of law, when an expert witness is asked to testify as to whether a lung nodule or mammographic lesion should have been seen on a prior study. That study may have been performed one or more years earlier. The current study shows an obvious abnormality, making the less obvious version of the lesion on the prior exam easier to see. It’s not easy to know if the radiologist reading the prior study should have been expected to see the abnormality because it’s impossible to replicate the exact circumstances of the prior reading.

Another radiology analogy relates to the volatile swings in the radiology job market. Medical students either shy away from or run to radiology, depending on the current number of available jobs. We can’t predict when the radiology market will be up or down any more than we predict what the financial markets will do.

5. We see patterns where none exist.

As financial markets bounce up and down, we tend to extrapolate recent returns and assume the rising markets will continue to rise (prompting investing more) or that falling markets will continue to fall (prompting selling, often in a panic). The problem with this behavior is that we can’t predict what the markets will do and often wind up buying and selling at the wrong time instead of following a strategy of long-term investing. Over a long period of time, day-to-day market fluctuations don’t matter.

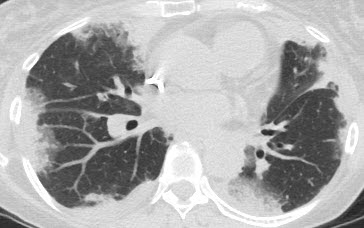

In radiology we’re used to making diagnoses based on patterns. It’s a useful strategy for narrowing the differential diagnosis. For example, a pattern of peripheral lung opacities on a chest CT suggests organizing pneumonia (shown in the image above), eosinophilic pneumonia, pulmonary infarcts, or traumatic contusions. Patient history, along with the radiologic pattern, often allows us to make a specific diagnosis.

A potential pitfall of using a pattern approach is not appreciating that a diagnosis will not always follow a specific pattern.

6. We hate losing.

In cognitive psychology and decision theory, loss aversion refers to people’s tendency to prefer avoiding losses to acquiring equivalent gains: it is better to not lose $5 than to win $5. Studies suggest that the win would have to be twice as much ($10 in this case) as the loss to get us make the bet, even though we know that a $5 win would make it a fair bet. This distaste for losses helps explain why investors have, historically, shied away from investing in stocks, despite their superior long-term gains. There’s a good reason so many millennials (i.e. born between 1981-1996) are hesitant to put their savings into the stock market. Many of them lived through two market crashes, and coupled with a human tendency for loss aversion, don’t want to take on what to them is unreasonable risk.

7. We sell winners and hang on to losers.

We don’t like to sell a stock or fund for less than what we paid for it (another example of how we are loss averse). We like to sell winners, and brag about it. Holding a loser can be rationalized (“it’s only a paper loss”) but selling would be like admitting we made a mistake. This is psychology ruling investment behavior, when our actions should be based on a sound financial plan. As the dotcom bubble taught a lot of people, sometimes it’s best to sell something that was never a good investment in the first place, even if it means locking in a loss.

8. We’re overconfident.

Self-attribution refers to a tendency to make choices based on one’s self-confidence in their knowledge of something. Most of us think of ourselves as above-average, which can be a positive trait if it means we’re happier and better able to succeed in life. It becomes a handicap when excessive self-confidence, say in our ability to time the market, leads to making bad bets.

I remember talking to a pulmonologist colleague of mine many years ago about one of the radiologists we both knew. She described him as “always sure and sometimes right.” Radiologists do not always know the answer/diagnosis and to imply otherwise sets unrealistic expectations for trainees and others for whom they serve as role models.

9. We take credit for our winners, while blaming our losers on others.

If our investment goes up, it was because we made a brilliant choice. If it goes down, it was because someone gave us bad advice. This reaction to winning and losing reduces the chances that we will learn from our mistakes, while further bolstering our self-confidence.

As a radiologist, sometimes I make a great call, most of the time I make the same good call that any reasonable radiologist would make, and sometimes I miss something that I shouldn’t have. It never feels good to get that email or phone call to inform you that you missed a lesion or misinterpreted a finding on a CXR or CT scan. Errors and discrepancies in radiology practice are uncomfortably common, with an estimated day-to-day rate of 3–5% of studies reported, and much higher rates reported in many targeted studies. But knowing that it happens to all radiologists and looking at it as an opportunity to learn so as not make the same mistake again lessens the pain.

10. Our risk tolerance isn’t stable.

We develop a portfolio, in part, based on our tolerance for risk. If we are particularly risk averse, we might invest more in bonds and less in stocks. But as too often happens, our risk tolerance changes when tested by a market crash, and we sell our investments in order to prevent further loss. Then we don’t know when to get back into the market, or we do so when the market has already fully recovered. This creates a “buy high, sell low” pattern of investing that erodes returns over the long run.

Radiologists are risk averse in that they don’t want to miss an important finding on a radiologic exam or harm a patient when performing an imaging-guided procedure. Mammographers represent a cohort of radiologists with a wide range of risk tolerance. In one study, the mammography recall rate (calling an abnormality on a mammogram) ranged from 5% to over 14%. I’ve known some mammographers with recall rates over 20%. Although there are several factors that influence the recall rate, one of them is the unease associated with the possibility of missing a cancer. This can lead to overcalling, resulting in more women having to return for additional testing. With greater experience and training, mammographers can lower their recall rate to a locally acceptable number.

11. We get anchored to particular prices.

In 2018 I bought a house for $125,000 less than the sellers paid for it 12 years earlier. They felt “sick about it but just wanted to move on” after trying to sell the house on and off for the past 3 years for a price closer to what they paid. Unfortunately, they bought the house during the height of the housing bubble. Housing prices peaked in early 2006, started to decline in 2006 and 2007, and reached new lows in 2012.

It’s hard to take a big loss, especially in the housing market since it isn’t uniform across the country. If it was, you could sell a house in one place, at a loss, but buy a comparable house in your new location, at the same “bargain” price. It would be a wash.

12. We rationalize bad decisions.

It’s human nature to rationalize bad decisions, even going so far as to change our recollection of the past. Knowing that we made a stupid financial decision but also believing that we are smart about handling money are contradictory thoughts, an example of “cognitive dissonance.”

13. We favor familiar investments.

Have you ever heard someone say they own Apple stock because they love their iPhone, or Chipotle because they love their burritos, or Nike because they live in Beaverton? This kind of familiarity makes these stocks more comfortable to own, but using this as a strategy for investing can result in a badly diversified portfolio with unnecessary and uncompensated risk.

In radiology, especially academia, I’ve gotten used to hearing about “the (fill in the university name) way.” It’s the answer to a lot of questions as to why things are done the way they are: how the clinical rotations are scheduled, what time resident conferences occur, how much “study time” residents have before a board exam, how studies are read (and by whom) on call, how CT scans are performed, how salaries are determined, and so on. Some customs are department specific and some dictated by the hospital/university/corporation.

Radiologists tend to stick to what they were taught during training and how others in their group practice.

It’s not that change doesn’t happen. But how often are changes made proactively as opposed to being mandated? How many radiology groups would willingly adopt an appropriate use criteria (AUC) program if it wasn’t mandated by the government in order to collect Medicare payments? Even though it’s not hard to convince physicians in all the appropriate specialties that it makes sense to order radiologic imaging examinations based on accepted criteria, it’s a whole other thing to convince them and the administration to accept the costs and “growing pains” associated with implementation. We tend to fall back on our friend “status quo.”

Humans are averse to change for a variety of reasons – loss of control, uncertainty, defensiveness, more work, less work, just to name a few. One of the biggest conceived threats to radiology today is how artificial intelligence will affect the practice of radiology (and medical student interest in the field).

14. We put a higher value on investments we already own.

This is known as the endowment effect. We are reluctant to sell investments or property that have special meaning, often because of the time invested in the purchase or an emotional attachment, such as with an inheritance. This can lead people to hold on to a bad investment.

15. We prefer sins of omission to sins of commission.

It’s often easier to do nothing. This is referred to as “status quo bias.” We feel worse if we sell an investment, which then soars in value, than if we didn’t sell an investment, which then falls in value. This phenomenon is similar to that of “paralysis by analysis”, which is the state of over-analyzing (or over-thinking) a situation so that a decision or action is never taken. I’ve known people who were thinking about cutting ties with a financial advisor, whom they knew was probably not offering good advice at a fair price, because they were afraid of the alternative (e.g., making bad decisions on their own or hiring a different advisor who was no better or might be even worse than the one they had).

Radiologists can get sued for missing a lesion (omission) or misinterpreting a lesion (commission).

When dictating a CT scan, would you feel worse not mentioning a finding that you thought (but wasn’t sure) was normal, or mentioning it knowing that it might make you look incompetent to your peers? If the finding was present on a scan performed one month earlier, and the radiologist who interpreted the study didn’t mention it, would that make you feel better about not mentioning it? What if the last radiologist “missed” the finding?

Here’s another analogy. I’ve attended a lot of radiology department education committee meetings. One topic that has come up over and over again is the problem with residents not attending conferences. This is never on the agenda. The discussion is always a result of getting side-tracked when talking about something else. I wonder how much time has been spent “venting” about this issue. Various solutions are bandied about. But in the end, it always seems easier to do nothing than risk turning one problem into another.

16. We find stories more convincing than statistics.

Have you ever bought a lottery ticket? According to a 2017 survey, 49% of U.S. adults reported buying lottery tickets. About 53% of those earned over $90,000 a year, so it’s not just poor people playing the game. And the wealthier players are more likely to be drawn in by the big jackpot prizes like those being offered by both Powerball and Mega Millions. While a $1,000 prize on a scratch off game isn’t going to be life changing to most practicing radiologists, a $500 million prize is real money for almost everyone.

What propels people to pay money for an almost certain chance of winning nothing? In part, it’s the frenzy associated with a prize that gets bigger and bigger every day – the story wins out, even though statistically, it makes no sense to play. The story makes it fun. Have you ever heard someone brag about how they just bought X shares of “whatever is the latest hot stock”? The chance to win big, even if very small and not backed by data, is the lure. Wouldn’t it be a great story to tell the grandkids – that you made a million dollars on a hot stock trade?

The radiology world is full of anecdotes and case reports, which are interesting and can lead to further discovery. But they shouldn’t influence day to day practice. Radiologic interpretations and decisions should be based on the best data available, which stems from research that is free of bias and generalizable to all populations.

17. We base decisions on information that’s easily recalled.

The memory system plays a key role in the decision-making process because individuals constantly choose among alternative options. Due to the volume of decisions made, much of the decision-making process is unconscious and automatic. Recall (or recency) bias (aka, “availability heuristic”) says that if you recall something, it must be important — or at least more important than an alternative not as easily recalled. That means we tend to give heavy weight to recent information and form opinions and make decisions biased toward whatever is recent.

For example, if you read about a shark attack, you’ll naturally decide shark attacks are on the rise — even if no others have occurred in the past six months. It’s recent, therefore it’s a trend. Or if you read about fighting in Syria you might think we’re living in exceptionally violent times, when in fact we’re living in the least threatening period in history.

An experiential bias occurs when investors’ memory of recent events makes them biased or leads them to believe that the event is far more likely to occur again. For example, the financial crisis in 2008 and 2009 led many investors to exit the stock market. Many had a dismal view of the markets and likely expected more economic hardship in the coming years. The experience of having gone through such a negative event increased their bias or likelihood that the event could reoccur. In reality, the economy recovered, and the market bounced back in the years to follow.

When we hear about someone who just won the lottery or made a fortune in real estate, it makes it seem like the odds of winning the lottery or amassing wealth from real estate seem far more likely than they are. Many people have tried to mimic the investment strategy of Warren Buffet, the “Oracle of Omaha”, who is viewed as one of the most successful investors in history and has amassed a multibillion dollar fortune mainly through buying stocks and companies through Berkshire Hathaway. Those who invested $10,000 in Berkshire Hathaway in 1965 are above the $50 million mark today. Wouldn’t that want to make you run out and invest all your money in the same thing? But alas, if it was as easy as that, we’d have a lot more billionaires in the world. Warren Buffet, himself, suggests that the average investor would do best by investing in low-cost broadly diversified mutual funds.

Radiologists are prone to recall bias after attending a mulit-disciplinary conference to discuss patient cases. Suddenly every lung opacity on chest CT is EVALI (E-cigarette Vaping Associated Lung Injury) or whatever disease was talked about at the conference. It also explains why radiologists are more familiar with the diseases that are common in their community and less so with those that occur in other environments.

18. We latch onto information that confirms what we already believe.

And at the same time, we ignore information that contradicts our beliefs. When there’s a wide range in a stock’s share price over a year’s time, some will look at that as a good opportunity to make money and some as a way to lose a lot of money. People tend to interpret information to make it match what they want it to be. In politics it’s called spin.

Confirmation bias is when investors have a bias toward accepting information that confirms their already-held belief in an investment. If information surfaces, investors accept it readily to confirm that they’re correct about their investment decision—even if the information is flawed.

We perform research to try to prove what we believe is true. When research confirms our theory, it’s a positive result. If not, it’s a negative result. Studies with positive results are more greatly represented in the radiology literature than studies with negative results, producing so-called publication bias. Underreporting of negative results introduces bias into meta-analyses, which consequently misinforms researchers, doctors and policymakers.

19. We believe there’s safety in numbers.

This is also referred to as “herd mentality.” Purchasing investments that everyone else is buying can make investing seem less frightening. But while popularity may be a useful guide when picking a restaurant or choosing a movie, it can be a disaster when investing, because we can find ourselves buying overpriced investments that may add uncompensated risk (e.g., individual stocks).

Radiologists are not immune from herd mentality. If two different radiologists said the calcifications seen on prior mammograms were benign, or that the ground glass nodule seen on prior chest CTs was benign, we feel comfortable agreeing with them. Safety in numbers.

20. Our financial decisions aren’t purely financial.

People make financial decisions for more than utilitarian reasons. Owning a hedge fund with high costs may make a person feel important, even if those high costs make it unlikely that the fund will beat market returns. Some people feel good about investing in socially responsible funds, even though they may not provide optimal returns compared with alternative funds. Back in the 1990’s I personally knew several people who were actively day-trading. It was thrilling to them, and they were making lots of money. Until they weren’t.

Radiologists are not immune to letting external factors or emotions influence their practice. Have you ever read your mother’s CT scan? Did emotion come into play or did you read it with the same objectiveness as you read any other scan? What about reading a study or performing a procedure on a VIP? Do you treat this person any differently than any other patient? I’ve had doctors call me to tell me that the chest CT I’m reading is that of the CEO of the hospital. What should I do with that information?

21. We engage in mental accounting.

One of the best examples of this is focusing on the performance of individual funds or accounts rather than on the entire portfolio. The whole reason behind having a diversified portfolio is to lessen the impact when one type of investment class (e.g., stocks, bonds, real estate) loses value. But some people find it hard to ignore investments that are currently in a slump. This leads to anxiety and in some cases, to selling those investments at a loss.

22. We’re influenced by how issues are framed.

People are more likely to contribute to a 401(k) plan if they are automatically enrolled (and can opt out) rather than having to choose to contribute. There are a couple reasons for this. When someone has to opt in, they have to actively make a decision as opposed to letting someone make it for them. Automatic enrollment uses human inertia to the employee’s advantage. It’s human nature to “follow the path of least resistance.” Once enrolled, a person has to overcome inertia to un-enroll. There’s also a feeling that if it’s a company policy to automatically enroll new employees, it “must be a good thing to do.”

We could get a lot more radiologists to participate in Image Wisely, peer-review programs, etc. if it was an opt-out rather than opt-in activity.

Here’s another analogy. One of the components of consenting a patient for a procedure is discussing the potential adverse effects. Pneumothorax is the most common complication of needle aspiration or biopsy of the lung, which in one study was reported to occur in 17–26.6% of patients. Only 1% to 14.2% will require chest tube insertion. What is the best way to relay this to the patient? You could say, “as many as 26% of patients get a pneumothorax and up to 14% will need to have a chest tube placed.” Or you could say, “in the best of hands (yours of course), 73% of patients will not develop a pneumothorax and 99% will not require a chest tube.” You’re delivering the same information in both scenarios, but the patient will interpret that information differently depending on whether it’s framed positively or negatively.

There are plenty more examples that could be associated with each of the items listed above. I’d love to hear your favorites – shoot me an email and if I get a good list I can update my post.

For further reading on this topic, I suggest the following excellent book:

Clements J. How to think about money. Published by Jonathan Clements, LLC. 2016.