Building Your Stay-well Game Plan: Health, Long-term Care Insurance

Thus far, we’ve taken a jaunt through the educational pastures of life and malpractice insurance, and dipped our toes into the informative waters of disability insurance. In this post, we shall take a stroll of insight through the valley of health and long-term care insurance.

Fortunately, or unfortunately, I am neither a gecko nor Dennis Quaid (or insurance spokesperson of any kind). So I’ll just get right to it. Here are some important things you should know:

Health insurance is a must. The potential consequences of contracting a major illness without having insurance can be catastrophic. All medical care is expensive and even more so if you don’t have insurance and have to pay the full, non-insurance-negotiated rate. Even minor health events can result in 5-figure charges. You can’t get a federal loan to pay for medical care like you can for college tuition. Many people without insurance resort to putting medical costs on a credit card, which results in an even larger bill when interest rates are tacked on. Two-thirds of people who file for bankruptcy cite medical issues as a key contributor to their financial downfall. People without insurance avoid getting medical care, which in some cases can lead to a delayed diagnosis.

By investing in decent health insurance and also, potentially, long-term care insurance, you can help ensure you’re better able to receive the quality care you may need, while maintaining both your physical and financial health and wellbeing.

Medical students and residents are offered insurance through their university and employer, respectively. The premiums, deductibles, out-of-pocket maximums, and coverage types are variable from institution to institution. In general, the costs are reflective of student unemployment and a resident’s salary. The premiums I’ve seen range from $0 to $150 for individual coverage and up to $500 for family coverage. This is a bargain compared with what it costs for a non-subsidized plan on the open market. Some institutions offer both high deductible and non-high deductible plans.

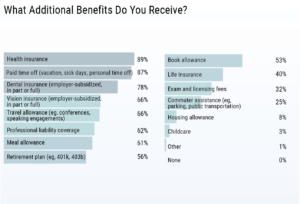

The majority of residents work in a hospital and receive their salary and benefits from the hospital. The illustration below shows that 89% of residents receive health insurance.

Medscape Residents Salary and Debt Report 2019

Practicing radiologists receive health insurance benefits through their employer, or buy it individually if they are self-employed or don’t have access to a good group plan. Radiologists at academic institutions get their insurance through the associated university. Those in group practice may or may not get insurance through their group, depending on the size of the group. Many groups are too small to offer group insurance. Or, in some cases, buying insurance on the open market may be cheaper than what the group is offering.

Picking your purveyor

Most radiologists who buy individual plans will buy it through a health insurance broker instead of through the open marketplace on healthcare.gov since it doesn’t cost more and they won’t qualify for a subsidy. Health insurance is very expensive and over the past 5 years, I’ve seen the prices increase and the options decrease. When you go from getting insurance from an employer to buying it on your own, you appreciate how much of the premium an employer picks up.

Greener grass outside the group plan?

When I became self-employed, I initially bought insurance through the marketplace. Although the coverage and cost was exactly the same as buying it through an agent (or directly through the insurance company), the marketplace allowed me to buy better dental insurance at a lower cost than what I could get on my own. However, dental coverage through the marketplace changed, and the last time I looked, buying it through the marketplace offered no benefit. I also found that working with the marketplace was a big hassle. When I moved, for example, I talked to several people from the marketplace who didn’t seem to know how to let me transfer from an OH plan to a WI plan without incurring a lapse in coverage.

I’m now able to get my insurance through the State of Wisconsin Group Health Insurance for Retirees. The coverage is the same as what I can get on my own, but the premiums and deductibles are lower. And since I’m self-employed, my premiums are an above-the-line income tax deduction (meaning my taxable income is reduced by the full amount of the premiums).

A word about dental and vision

I buy dental insurance outside of the group plan because it’s cheaper and offers benefits that are just as good. The amount of my premiums are a little less than the cost of twice a year cleanings and x-rays. And the type of insurance I have gives me a discount on dental work. This works for me since the insurance covers a large number of dentists in my area that I’m willing to see. Another big advantage of having dental coverage is getting the insurance-negotiated rate for services, which can be much less than paying full-price for dental work.

Vision insurance is offered by many group plans and is also available to purchase individually. I pay for vision insurance through my state group plan because the premium is minimal and more than covers an annual comprehensive eye exam, which is recommended for someone of my age. If I didn’t need eye exams I wouldn’t pay for the coverage, since I don’t need a discount on glasses or contacts.

Picking a plan (and comparison shopping)

You’ll encounter some alphabet soup while shopping for health insurance; the most common types of health insurance policies are HMOs, PPOs, EPOs or POS plans. The kind you choose will help determine your out-of-pocket costs and which doctors you can see.

COMPARING HEALTH INSURANCE PLANS: HMO VS. PPO VS. EPO VS. POS

| Plan type | Do you have to stay in network to get coverage? | Do procedures & specialists require a referral? | Snapshot: |

| HMO: Health Maintenance Organization | Yes, except for emergencies. | Yes, typically | Lower out-of-pocket costs and a primary doctor who coordinates your care for you, but less freedom to choose providers. |

| PPO: Preferred Provider Organization | No, but in-network care is less expensive. | No | More provider options and no required referrals, but higher out-of-pocket costs. |

| EPO: Exclusive Provider Organization | Yes, except for emergencies. | No | Lower out-of-pocket costs and no required referrals, but less freedom to choose providers. |

| POS: Point of Service Plan | No, but in-network care is less expensive. | Yes | More provider options and a primary doctor who coordinates your care for you, with referrals required. |

When comparing different plans, consider the amount and type of treatment you’ve received in the past. Though it’s impossible to predict every medical expense, being aware of trends can help you make an informed decision.

HMOs tend to be the cheapest type of health plan. Over the past few years, more and more insurance providers are offering only HMO plans with no coverage for out-of-network service. It’s very important to look at the hospitals, doctors, and clinics within the HMO to see if they provide options you would be satisfied with. Costs are lower when you go to an in-network doctor because insurance companies contract lower rates with in-network providers. When you go out of network, those doctors don’t have agreed-upon rates, and you’re typically on the hook for a higher portion of the cost.

Weighing your options: benefits, costs

If you have preferred doctors and want to keep seeing them, make sure they’re in the provider directories for the plan you’re considering. You can also directly ask your doctors if they accept a particular health plan, although be ready to get an equivocal answer. In my experience, the people who answer the phone at your clinic or doctor’s office aren’t always able to tell you if you are in their network. What’s more, there is nothing to prevent a doctor or doctor group from leaving the network after you’ve enrolled.

A high-deductible health plan (HDHP) can be any one of the types above — HMO, PPO, EPO or POS — but follows certain rules in order to be “HSA-eligible.” These HDHPs typically have lower premiums, but you pay higher out-of-pocket costs. They are the only plans that qualify you to open a health savings account (HSA), which is a tax-advantaged account you can use to pay health care costs. HSAs are also a great way to save money for retirement since the contributions are tax deductible, you don’t pay taxes on the growth, and when used for qualified health care expenses, the dollars are not taxed at withdrawal. And you can withdraw HSA dollars anytime in the future for health care expenditures that you pay out-of-pocket for today.

If you don’t have a preferred doctor, look for a plan with a large network so you have more choices. A larger network is especially important if you live in a rural community, since you’ll be more likely to find a local doctor who takes your plan. When looking at different plans, compare what they cover, particularly for things like physical therapy, maternity care, drug coverage, fertility treatments, mental health care, and emergency coverage.

As the consumer, your portion of costs may include deductibles, copayments and coinsurance. A deductible is the amount you pay each year for most eligible medical services or medications before your health plan begins to share in the cost of covered services. A copay is a flat fee that you pay on the spot each time you go to your doctor or fill a prescription. Coinsurance is a portion of the medical cost you pay after your deductible has been met. For example, if your coinsurance is 20 percent, you pay 20 percent of the cost of your covered medical bills and your health insurance plan will pay the other 80 percent.

A plan that pays a higher portion of your medical costs, but has higher monthly premiums, may be better if:

- You see a primary physician or a specialist frequently.

- You frequently need emergency care.

- You take expensive or brand-name medications on a regular basis.

- You are expecting a baby, plan to have a baby or have small children.

- You have a planned surgery coming up.

- You’ve been diagnosed with a chronic condition such as diabetes or cancer.

A plan with higher out-of-pocket costs and lower monthly premiums might be the better choice if:

- You can’t afford the higher monthly premiums for a plan with lower out-of-pocket costs.

- You are in good health and rarely see a doctor.

Long-term care insurance

Here’s a hair-raising statistic: a 65-year-old couple retiring in 2019 can expect to spend $285,000 in healthcare and medical expenses throughout retirement.

This doesn’t include the additional annual cost of long-term care, which, in 2019, averaged from $19,500 for adult day care services to $102,204 for a private room in a nursing home.

The concept of long-term care (LTC) has been evolving over the past 20 years and is now a mainstream consumer product.

So, what is it exactly?

The most widely-used definition of LTC focuses on the activities of daily living, or ADL (dressing, bathing, eating, walking, and using the bathroom). A popular standard states that a person needs LTC when they require assistance with two or more of the ADL.

According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 70% of those turning age 65 today will need some type of long-term care. LTC insurance is coverage that will pay for assisted living, nursing home care, or home health care in the event you are unable to care for yourself because of a chronic condition or disability.

Another hair-raising point? It’s not traditionally covered by Medicare.

You can’t count on Medicare to pay for nursing home, assisted living, or ongoing home health care. Medicare benefits for that type of care are typically only available after a hospitalization or injury and for a limited duration.

Now, for a “tear-your-hair-out” kind of point: LTC insurance is expensive.

For example, a 65-year-old couple might purchase a policy that will give them base benefits of $180,000 plus 3% inflation growth that will cost them $4,800 per year. The price for that same plan more than doubles to $8,700 per year if the couple waits until age 75 to buy. Others may have health conditions that make them ineligible for coverage at any price. The average age of a buyer today is 57, down from 67 when policies were first being sold. It’s easy to see why. Premium prices steadily go up with age but take a sharp turn at age 65, when they begin to rise by about 8% a year.

And the rates can go up after purchase, by as much as 70% annually on older policies. Whew! Why are the rates so high? Rate hikes seen on older policies (sold in the 1990’s and early 2000’s) are the result of faulty assumptions about the number of claims that would be made and how many policies would lapse. Also, some insurers did little to no underwriting in the early years, making it possible for virtually anyone to buy coverage regardless of the probability of them filing expensive claims in the future.

The good news? Since that time, long-term care insurers have made significant changes in how they issue and price their plans. They now have decades of claims data to base their underwriting, so premiums should theoretically become less volatile.

Who should purchase LTC insurance?

The rule of thumb is that you’re a candidate to buy LTC insurance if you have between $200,000 and $2M in assets.

There are three categories of people to consider when contemplating this question:

- Individuals of modest means. They can’t afford LTC insurance and can’t self-insure. Medicaid was created to provide LTC for this group, who will spend their modest assets until they qualify for Medicaid, and then they rely on the government to pay for the rest of their care.

- Individuals on the opposite end of the wealth spectrum. They do not need LTC insurance because they can pay for any needed LTC comfortably out of income and assets.

- The people in the middle. But what is the dividing line? Where’s the donut hole? That’s the ultimate question. The rule of thumb is that you’re a candidate to buy LTC insurance if you have between $200,000 and $2M in assets. With less, you can’t afford the premiums and don’t have enough to protect. With more, you can reasonably plan on paying your own way.

Group Long-Term Care Insurance

You may be offered group coverage as a voluntary benefit at work, although this benefit is not yet widespread. Given the problems with LTC insurance policies (e.g., high cost, unpredictable premium increases, and insurer solvency, just to name a few), most radiologists are choosing to self-insure, meaning they save up the cash they will need for future long-term care costs.

Life/Long-Term Care Insurance

Life insurance policies that include long-term care riders have become very popular. A combination life insurance policy simply adds a long-term care rider to a permanent life insurance plan. The American Association of Long-Term Care Insurance said that more than 350,000 Americans purchased long-term care coverage in 2018. The vast majority (84%) of these purchases were for hybrid or combination life insurance. Only 16% were traditional long-term care policies.

If you read my post on life insurance you know that I don’t generally like mixing investing with insurance. These hybrid plans have positives and negatives:

Positives:

- You don’t face large rate hikes that can happen with stand-alone long-term care insurance

- You combine life insurance and long-term care insurance into one policy (i.e., it offers convenience)

- You get life insurance protection

- Survivors get money not spent on long-term care

Negatives:

- Not available with term life insurance (which means you’re mixing insurance with investing)

- Lower payout than stand-alone long-term care insurance

- Can be more costly than stand-alone long-term care insurance (which is already expensive)

- Paying with one lump sum, which will give you the cheapest rate, is expensive

The combo approach may be a good idea when there are underwriting issues involved (i.e., you don’t qualify or are a poor candidate for either term life insurance or long term care insurance).

Another option – CCRC

Continuing care retirement communities, also known as CCRCs or life plan communities, are a long-term care option for older people who want to stay in the same place through different phases of the aging process. There are nearly 2,000 continuing care retirement communities in the U.S. offering different types of housing and care levels based on a senior’s needs and how they change. A CCRC resident can start out living independently in an apartment and later transition to assisted living to get more help with daily activities, or to a memory care unit or skilled nursing to receive more medical care while remaining in the same community.

The chief benefit of CCRCs is that they provide a wide range of care, services and activities in one place, offering residents a sense of stability and familiarity as their abilities or health conditions change. But all this comes at a cost. Nearly two-thirds of the communities charge an entry fee, averaging $329,000, but topping $1 million at some CCRCs. Once residents move in, they pay monthly maintenance or service fees that typically run $2,000 to $4,000.

There are many permutations to how CCRCs function and charge for services, including the following options: 1) a full range of services but high fees (e.g., unlimited assisted living, medical treatment and skilled nursing care with little or no additional cost), 2) a limited set of services, beyond which the resident incurs higher monthly fees, and 3) a fee-for-service contract, where residents pay for whatever specific services that they require.

Because a lot of money is on the line, buyers should investigate a CCRC thoroughly before signing a contract. You don’t want to commit to living out your life in a place that you discover is poorly managed and financially unstable.

Many of the highly sought-after CCRCs have a waiting list and require a deposit. After investigating all the CCRCs in our area of interest, my husband and I put down a $1,000 deposit at the facility we liked best that provides all levels of care. The waiting list is long and on average, it is 7 years before an independent living unit is available. The entry fee for life lease apartments (independent living) ranges from $229,900 to $570,300, and the monthly fees range from $2,017 to $2,761 for a single person (2019 rates). The daily rates for higher levels of care are $231 per day for assisted living, $291 per day for memory care (private room), and up to $418 per day for skilled nursing care.

The average 65-year-old will need three years of LTC, with about ⅔ of that time spent at home, and the rest in either a nursing home or assisted-living facility. All of those levels of care can be obtained at a CCRC, but as you can see, it comes at a significant cost. One year of skilled nursing comes to $152,570 in the example above.

To recap…

Everyone needs health insurance. If you’re lucky, you get good coverage at a reasonable price through your employer. Or you can easily afford to purchase a good individual plan. The high cost of individual health insurance influences many a radiologist’s decision to work for an employer versus be self-employed, as well as when to retire. Medicare doesn’t kick in until age 65! Long term care insurance is not as straightforward and given its limitations, and the average radiologist’s wealth, most radiologists will decide to self-insure.

Next up? Home and auto insurance, and extended warranties. I’ve included some information that should be interesting for everyone. If for no other reason, you’ll want to read the next post just to be entertained by my personal anecdotes.