What in the Heck is a “Bull Market” and a “Bear” Market”?

Imagine yourself skipping down a yellow brick road. That road has a street sign that says, “Wall Street.” You’re on a journey to the Emerald City, which you presume is so-named for all its flourishing investments and wealth; a place where money is so abundant it practically grows on everything and little green triangles always point skyward. Along the way, the sky begins to darken. Suddenly, you feel spooked and uneasy. Despite your fear, however, you know you must be brave and carry on, so you begin to sing a little ditty. This makes you feel better, and eventually, you arrive at the destination of your dreams.

The ditty that gave you courage to get through the scary parts of the journey? Well, it goes a little something like this: “Bulls and luftsichel signs and bears, oh my!”

If I may preempt you, no, I have not been frolicking through a poppy field. The tale I’ve told you will all make sense in time, and in a circuitous way, encapsulates the lesson of this post. And also…the nature of the beast…

Alright, enough goofing; let’s get down to business!

Even if you don’t consider yourself to be a financial expert, you’ve probably come across the terms “bull market” and “bear market.” They’re hard to avoid. The terms are ubiquitous in newspapers, magazines, blogs, and TV news and financial shows.

Consider the following headlines:

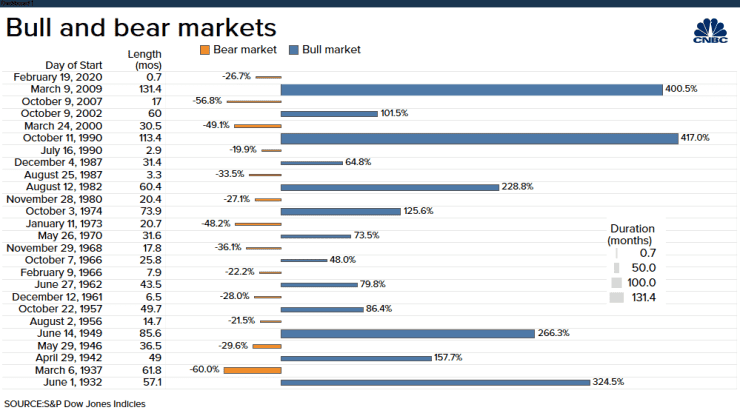

“With the stock market officially in a bear market, here’s a look back at each decline of at least 20% since the 1930s to see how long, and how severe, such downturns typically are.” (CNBC 3-14-20)

“Is this a new bull market? Or the same old bear? The rally has been historic, but it still needs to prove itself.” (Kiplinger 7-1-20)

Chart of the S&P 500’s returns in bull and bear markets

“Stock investors got the big bull market they wished for – and now they should be careful.” (Marketwatch 12-19-20)

If you don’t have a good handle on what these terms mean, don’t feel bad. You aren’t alone. I confess that I used to struggle with this.

Before I did a little research and became financially literate, this is the way I kept the terms straight: I pictured a bull as an animal raging forward (a stock market on the way up) and a bear as a lumbering, hibernating mass of inactivity (a stock market on the way down). I’ll leave it up to you to decide whether this makes any more sense than the real origin of the terms, which is coming up.

But first, a couple definitions

- an uncastrated male bovine animal (male cow)

- relating to, or resembling a bull, as in strength

- having to do with or marked by a continuous trend of rising prices, as of stocks (a bull market)

- a person who buys shares hoping to sell them at a higher price later

A bull is an optimistic investor who thinks the market, a specific security or an industry is poised to rise. Bulls attempt to profit from the upward movement of stocks by buying now under the assumption that they can sell later at a higher price.

A bull market is a period of time in financial markets when the price of an asset or security rises continuously. There is no specific or universal metric used to identify a bull market. A common definition is when stock prices rise by 20%, usually after a drop of 20% and before a second 20% decline. Other common measures are when at least 80% of all stock prices rise over an extended period or market indices rise at least 15%.

The most prolific bull market in modern American history started at the end of the stagflation era in 1982 and concluded during the dotcom bust in 2000. During this time the Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) averaged 16.8% annual returns. The NASDAQ, a tech-heavy exchange, increased its value five-fold between 1995 and 2000, rising from 1,000 to over 5,000.

A protracted bear market followed the 1982-2000 bull market. From 2000 to 2009, the market struggled and delivered average annual returns of -6.2%. Then, in March of 2009, the market began it’s start of a ten-year bull market run.

- any of a family of large heavy mammals of America and Eurasia that have long shaggy hair, rudimentary tails, and plantigrade feet and feed largely on fruit, plant matter, and insects as well as on flesh

- a surly, uncouth, burly, or shambling person

- a tall, friendly bear of a man

- something difficult to do or deal with

- having to do with or marked by a continuous trend of declining prices, as of stocks (a bear market)

- one that sells securities or commodities in expectation of a price decline

A bear market is characterized by a prolonged decline in the price of securities, typically by 20% or more from recent highs. But 20% is an arbitrary number, just as a 10% decline is an arbitrary benchmark for a correction.

Bear markets may accompany general economic downturns such as a recession. They can be cyclical or longer-term. The former lasts for several weeks or a couple of months and the latter can last for several years or even decades.

Another definition of a bear market is when investors are more risk-averse than risk-seeking.

Investors can take a bullish or bearish stance, depending upon their outlook. To be bullish is to believe that an investment’s price will rise. To be bearish is to believe that the price will fall.

Between 1900 and 2018, there were 33 bear markets, averaging one every 3.5 years. A prolonged bear market occurred between 2007 and 2009 during the Financial Crisis and lasted for roughly 17 months. The S&P 500 lost 50% of its value during that time.

In February 2020, stocks entered a sudden bear market in the wake of the global coronavirus pandemic, sending the DJIA down 38% from an all-time high on February 12 to a low on March 23 in just over one month. During this “Coronabear” period, the Dow Jones fell sharply from highs close to 30,000 to below 19,000 in a matter of weeks. Note: as I write this on December 29, 2020, the DJIA is back up to 30,390.

Other bear market examples include the 1929 Great Depression and the bursting of the dot com bubble in March 2000, which wiped out approximately 49% of the S&P 500’s value and lasted until October 2002.

“Bear” and “Bull” explained by a bit of history

The bear came first. Etymologists point to a proverb warning that it is not wise “to sell the bear’s skin before one has caught the bear.” By the eighteenth century, the term bearskin was being used in the phrase “to sell (or buy) the bearskin” and in the name “bearskin jobber,” referring to one selling the “bearskin.” Bearskin was quickly shortened to bear, which was applied to buying and selling stock in a speculative manner.

The “bear” borrows stock, sells it, buys it back at a lower price (hopefully), and returns it to the lender in a specified time period. This technique, called “short selling” is done with the expectation that stock prices will go down and bought back at the lower price, with the difference from the selling price kept as profit. It’s a risky trade and can cause heavy losses if it does not work out.

For example, an investor “shorts” (borrows and sells) 100 shares of a stock at $94/share. The price falls and the shares are “covered” (bought back) at $84. The investor pockets a profit of $10 x 100 = $1,000. If the stock trades higher unexpectedly, the investor is forced to buy the shares at a premium, causing heavy losses.

As an alter-ego to the bear, a “bull” makes a speculative purchase in the expectation that stock prices will rise.

Another explanation for for the terms bear and bull markets – one that is probably more widely understood and represented by the illustration below, is the following:

The “bear market” phenomenon is related to the way in which a bear attacks its prey—swiping its paws downward. This is why markets with falling stock prices are called bear markets. The term “bull market” comes from the way in which the bull attacks by thrusting its horns up into the air (rising stock prices).

What does this mean for you?

So many people can say it better than I can:

There will always be bull markets followed by bear markets followed by bull markets. (John Templeton)

There are two kinds of investors, be they large or small: those who don’t know where the market is headed and those who don’t know what they don’t know. Then again, there is a third type of investor: the investment professional, who indeed knows he doesn’t know, but whose livelihood depends upon appearing to know. (William J. Bernstein)

Bull markets go to people’s heads. If you’re a duck on a pond, and it’s rising due to a downpour, you start going up in the world. But you think it’s you, not the pond. (Charlie Munger)

The last leg of a bull market always ends in hysteria; the last leg of a bear market always ends in panic. (Jim Rogers)

Bull-markets are born on pessimism, grow on skepticism, mature on optimism and die on euphoria. (John Templeton)

In a nutshell

When it comes right down to it, you don’t need to know what a bull market or a bear market is in order to make sound investment decisions. You don’t need to listen to the media and sell during a bear market and buy during a bull market (although, sadly, this is what many people do).

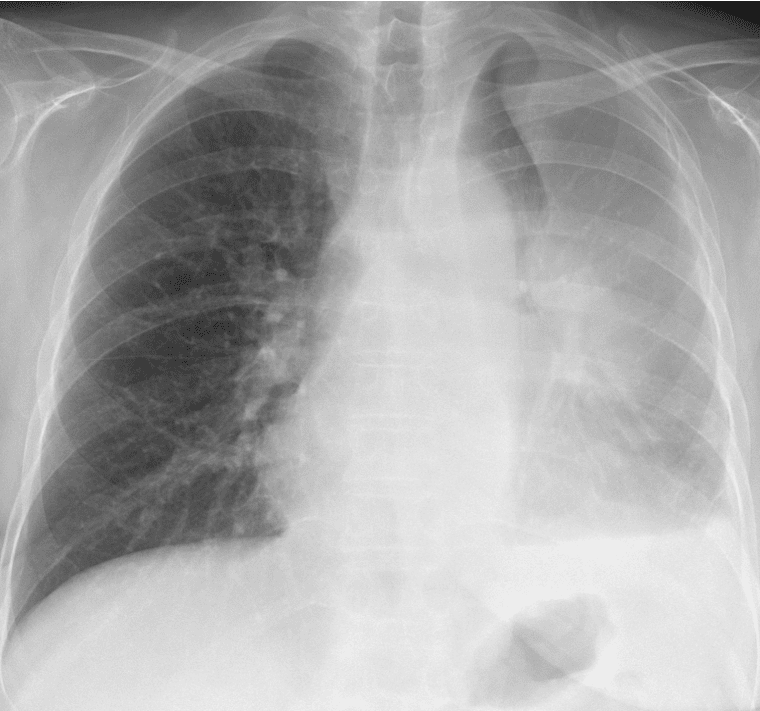

Upright CXR showing arcuate lucency surrounding the aortic “knob”

Then why did I write this post? For the same reason you should be familiar with the “luftsichel sign” of left upper lobe atelectasis on a CXR. You may know this as an arcuate lucency surrounding the aortic knob, representing the hyperexpanded superior segment of the left lower lobe interposed between the atelectatic left upper lobe and the aortic arch.

Do you need to recognize the luftsichel sign in order to diagnose left upper lobe collapse? Absolutely not. There are many other, more consistently seen signs of volume loss that allow you to make the diagnosis. But when your non-radiologist colleague or resident asks you if the lucency represents a pneumothorax or a pneumomediastinum, you need to be able to answer “no” and explain what the lucency represents. Or when they use the term luftsichel sign in a conversation, you need to know what they’re talking about.

Similarly, understanding “bull markets” and “bear markets” is not required in order to be a good investor. But if you do understand the terms, and someone mentions them in a conversation, you won’t feel like an idiot. And if they try to convince you that you should sell your mutual funds because we’re in a “bear” market, and the “market is only going to tank further”, you will know that that is a bunch of “bull”.