Highly Recommended Reading on Letters of Recommendation

You know how Netflix or Amazon recommendations sometimes make you feel like, wow, they’ve really nailed me? Well, fortunately or unfortunately, there is no such algorithm (yet) when it comes to education or career candidacy. A letter of recommendation (LOR) is a required and important component of an application for medical school, residency, and fellowship. It may be requested in written or verbal form for radiology jobs and is a key element of promotion packets.

Potential-newsflash: they actually really do matter! While it might feel like just another box to tick, don’t check-out when it comes to this important piece of the process. The quality of the letter can mean the difference between getting a position and not being considered. Maximum effectiveness of LORs depends on actions taken by both the person asking for the letter and the person writing the letter.

I’ll discuss each in succession, followed by a handy recap of key points. And as a bonus, I’ve provided a sample LOR. Feel free to plagiarize any part of it; I pinky-promise not to rat you out (technically it won’t be plagiarizing since I’m giving you my permission!). Whether you need to procure one or pen one, I’ve got you covered with the following helpful tips:

If you are asking for a letter of recommendation

Develop relationships

This should happen months or years before you need a letter of recommendation and is good practice for career-building in general. Although trite, the cliche “it’s not what you know but who you know that matters” is no less true. Ideally, a candidate will develop relationships with those who have influence in the field they wish to pursue or with those who can support a candidate’s promotion from a place of authority (e.g., section chief, department chair).

Don’t limit your support team to people in your own department or at your own institution. Email and social media has made it easy to develop relationships from afar. LORs from people outside the candidate’s institution may even be more highly considered by hirers or promotions committees because they speak to a candidate’s motivation and initiative.

Choose the right person

Choose people who can genuinely and with passion provide positive and meaningful comments about you. If anyone seems hesitant to serve as a reference, it’s probably best to exclude them from your list. Likewise, it doesn’t serve you well to ask a department chair or anyone else that you don’t have a relationship with to write a LOR. If they do agree to write a letter it might be short and impersonal. Ideally, a writer will be someone who can speak to your suitability for the role beyond which can be determined from reading your curriculum vitae (CV). A soon-to-be graduated trainee should only include supervisors as references (e.g., program director, chair, other faculty members, or research director)—those who are able to speak objectively and with authority about the trainee’s performance.

Prepare your CV

A radiologist’s CV should include contact information, licensing and board certification, past education and training, work experience (including dates, names, and locations of all prior radiology positions), professional appointments, awards and honors, teaching experience, publications, grants/other funding, research experience, and other career achievements as they are relevant to the job for which one is applying.

In the case of a new graduate, the CV should document the relevant education and training up to the time of the interview, including dates, degrees earned, and names of colleges and training programs going back to undergraduate college. Prior work experience should be included if it was professional in nature (e.g., working in a medical research laboratory, working as a school teacher or other profession prior to entering medical school).

Ask nicely

Pretty-please. It’s considered common courtesy to personally ask someone to write you a letter of support. This can be in-person or via email but should come from you. Personal requests demonstrate maturity and respect for the writer’s time and effort. A request from a third party (e.g., dean’s office, chair of a promotions committee) is impersonal and may lead to rejection or worse, to a less than glowing letter. Note: Some promotions committees require arms-length LORs and don’t allow the candidate to solicit the LOR. This doesn’t prevent you from giving a heads up to anyone you might have suggested as a possible reference.

Anything you can do to make the job easier for the letter writer will increase the odds of getting the letter you want.

Suggest language

Do some of the heavy-lifting first. Outline your most relevant accomplishments and share them with the letter writer. You can even draft a complete letter. Anything you can do to make the job easier for the letter writer will increase the odds of getting the letter you want. It also sends the message to the letter writer that you are organized and respectful of their time, both of which will make a good impression.

Provide instructions

If there is a deadline, be sure to share that. And make your request well ahead of the deadline. I suggest a heads up of 4-6 weeks. Writing a quality LOR requires ample time for consideration, reflection, and composition. Asking late in the process may suggest a lack of seriousness. Tell the letter writer about the position, why you want it, and why you are a good match. This will allow the writer to include specific supportive information. If the letter is for a faculty position, the writer should receive a copy of the published job description. If it’s for a promotion, the writer should receive a copy of the institution’s promotion criteria.

If there’s anything in your training/work history that could be construed as negative (e.g., a large time gap between jobs or leaving a job before securing another job), it’s best to address it head-on with the writer should they be asked about it.

Say thank you

Acknowledge the writer’s time and effort by thanking them for their support. When accepted into a medical school, matched into a residency, offered a job, or gotten the promotion, inform the writer of the good news. This closes the communication loop and demonstrates more than anything else the value of the writer’s contribution to your success. This kind of feedback fuels a writer’s motivation to help you again in the future and to help others.

If you are writing a letter of recommendation

Accept only if you are a good fit

Do you know the candidate? How much influence is your experience and role likely to have on the candidate’s success? You may agree to write a LOR even if you don’t know the candidate well, but you should draw a hard line at agreeing to write a letter if it will be negative. You know that saying, damning with faint praise? Well, it’s also true.

Only agree to write a LOR if it can be positive.

Make it honest and positive

Offer honest praise. Don’t exaggerate. State fact. Effusive letters about every candidate you write a letter for lessens your credibility as an honest and fair evaluator. Only agree to write a LOR if it can be positive. If that’s not the case, you can politely refuse, citing that you don’t know the candidate well enough or are otherwise not the best person to write a LOR.

Make it professional

Follow a professional template using professional stationery/letterhead. Although there is no one right way to pen a LOR, there are elements that every letter should include:

- Opening – an introductory statement describing the reason for the letter and the writer’s role and relationship to the candidate (e.g., teacher/student, colleagues, co-authors, shared committee work)

- Body – separate paragraphs that speak to the qualifications of the candidate as they relate to specific requirements for the role; if a promotion letter, each requirement for promotion should be specifically addressed

- Closing – a short 1-2 sentence summary of the candidate’s fit for the role or qualifications for promotion, often accompanied by how the candidate compares with other others who have applied for similar positions or gone up for promotion; a strong closing statement will rank the candidate as the “best” the writer has known or someone who would “definitely be promoted at the writer’s institution”

- Signature – a formal hand-written signature is often required and should be followed by the writer’s professional title (contact information should be included on the letterhead)

Make it personal

Ideally, the writer is familiar with the program the candidate is applying to, or has read the job description, or has reviewed the promotion criteria. The writer can then match a candidate’s unique skills and accomplishments to specific features of the program, job, or promotion requirements.

Referencing specific examples of a candidate’s behavior, performance, achievements, and awards as they relate to the job description or promotion requirements makes a stronger letter than one that provides only generalities or only information provided on the candidate’s CV. Tip: spend some time reading through the candidate’s CV and supporting documents, underline and jot down key items that can be emphasized and expanded on, and mull it over for a while before committing “pen to paper.” Seek and find brief but memorable ways of bringing the applicant to life.

For example, a letter can cull a few articles from the CV and discuss how they provided new information to the academic literature and how they impacted the professional community. This is particularly important if the candidate is going up for promotion based on scholarly activity and needs to show that they have pursued a focused area of research.

A description of the candidate’s teaching abilities can be personalized when they have been directly observed by the writer. This can be accompanied by audience comments and ratings. Online teaching can be documented by the number of students logged on and their geographical locations. This data will support the candidate’s national or international reputation.

Review the final product

A letter that is full of spelling and grammatical errors suggests less than full support from the writer. It may even indicate that the letter was drafted by an “assistant” and signed by the writer. A writer may choose to share the final draft with the candidate before it’s submitted. This allows the candidate an opportunity to correct inaccuracies or suggest additional supportive statements. Candidates are generally very grateful for this opportunity.

Recap

- Develop relationships throughout training and practice that can later be tapped for LORs

- Choose writers who know you

- Personally ask a potential writer for a LOR

- Discuss your CV, the position you seek, and why you want it with potential writers

- Thank the writer and let them know if you got the position or promotion

- Agree to write a LOR only if it can be positive

- Write letters that are professional yet personal, citing specific examples

- Describe why the candidate is a good fit for the position

- Carefully proof the LOR before it’s submitted

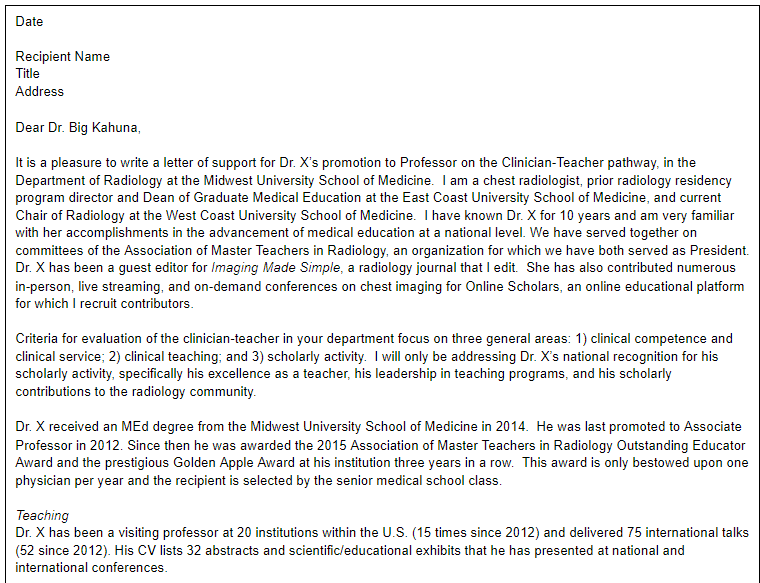

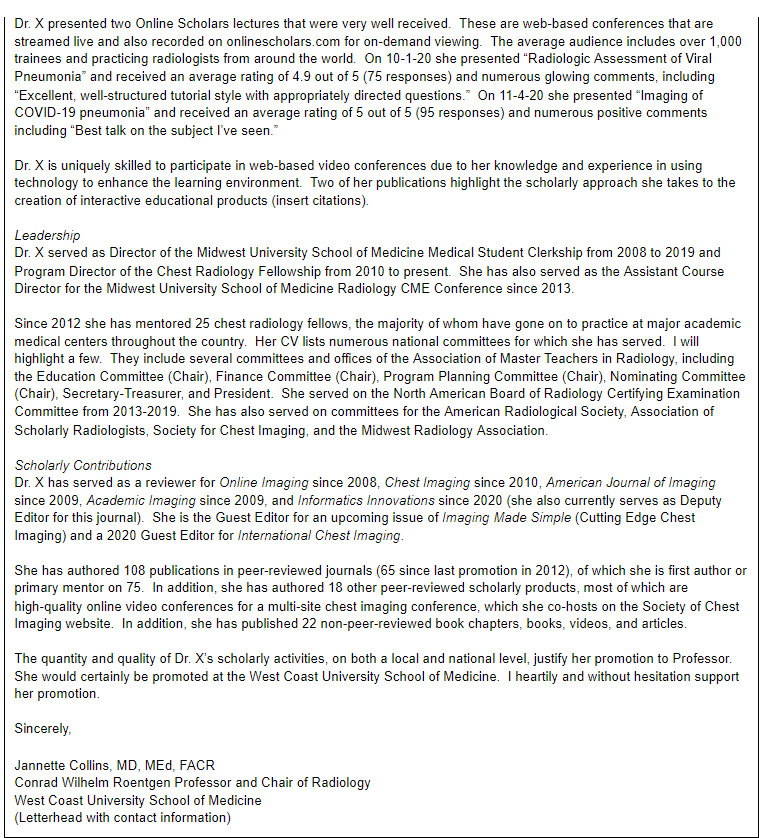

Sample promotion LOR

This example shows one way of organizing a LOR for someone pursuing promotion. A LOR for a student or trainee applying for medical school or residency/fellowship or a job will be different but still include the same basic elements: a brief description of the writer, her relationship with the candidate, and the reason for the letter; paragraphs describing the candidate’s specific attributes and achievements that support their fit for the role or justify promotion; and a strong summary statement that ranks the candidate with others.