Financial Capacity: Here Today, Gone Tomorrow (Wise-up on Health, Wealth, & Aging)

You may lose your marbles, but you can still preserve your financial well-being. Unlike other finance posts on The Reading Room aimed at helping you become financially literate, this one is all about what happens when you develop age-related financial vulnerability and are no longer able to make sound financial decisions.

And this post is not just relevant to older or retired radiologists, but also to those of you who are nearing that time of life or are/will be acting as an agent to manage finances for a friend or family member.

There’s a good chance that you will at some point be asked to manage someone else’s finances or will need someone to manage yours. If you are a working radiologist, you are probably already busy enough. Managing a loved one’s assets will be an added burden. Of course, the more informed you are, the better—and being as prepared as possible can help make that burden less overwhelming.

It’s an important and—okay, yes, somewhat depressing—subject. Growing older comes with it’s perks (wisdom, financial security, naps, etc.). It also brings greater susceptibility to a host of potential afflictions and new challenges to navigate—for both yourself and for your loved ones.

Hopefully, we will all undergo the aging process like a fine wine; stay sharp as a tack and still run marathons at 104, but we all know life is unpredictable. That’s why it’s vital to protect your financial health and security as a senior, and to know the risks and responsibilities involved when taking care of others.

In this post, I’ll talk about the scope of the problem, how aging and other factors can effect our financial abilities, the signs of financial vulnerability, tips for managing loss of financial capacity, how to recognize elder fraud and exploitation, and what you need to know before you agree to be a power of attorney.

How many people are at risk for age-associated financial vulnerability? Let’s look at the facts.

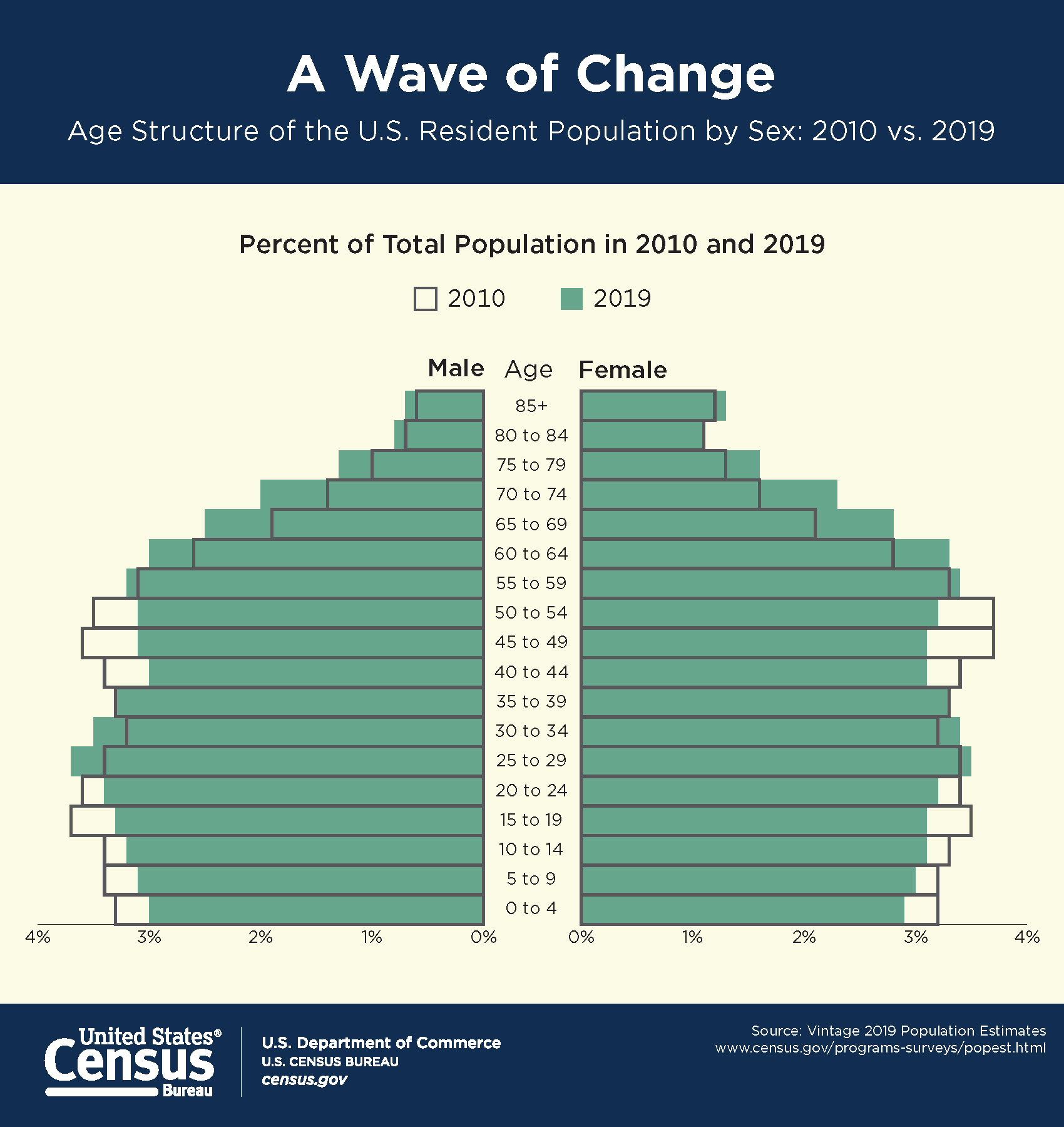

Source: U.S. Census Bureau

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, there were more than 54 million U.S. residents 65 years and older in 2019, up from 40.3 million in 2010. The number of Baby Boomers (born between 1946 and 1964) has hit 73 million, which has increased by 34.2% since 2010. Note: U.S. population in 2019 was 328,239,523.

Baby boomers have changed the face of the U.S. population for more than 70 years and continue to do so as more enter their senior years, a demographic shift often referred to as a “gray tsunami.” In 2019, one in five people in Maine, Florida, West Virginia and Vermont were age 65 or older.

What is the relationship between age and financial behavior?

When considering age-related changes in financial capacity, it’s important to understand the distinctions between normal aging, age-associated financial vulnerability, mild cognitive impairment, and dementia.

Although there are differences in abilities and rates at which individuals decline, everyone is expected to show some losses in fluid cognitive abilities. This includes memory, computations, and speeded decisions. These changes are typical of aging (i.e., “normal aging”) and not hallmarks of dementia or other disorders.

Age-associated financial vulnerability (AAVF) is defined as “a pattern of financial behavior that places an older adult at substantial risk for a considerable loss of resources such that dramatic changes in quality of life would result.” Note: To be considered AAFV, this behavior also must be a marked change from the kind of financial decisions a person made in younger years. For example, if you’ve been in the habit of leaving $1,000 tips throughout your career, this wouldn’t be considered an abnormal behavior just because you turned 65 years old.

Cognitively intact older adults may become financially vulnerable.

An important distinction should be made between AAVF and dementia or other cognitive impairments. Cognitive impairment is not necessary for AAVF. In other words, cognitively intact older adults may become financially vulnerable.

Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) is a disorder included in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. It is NOT considered to be a precursor to dementia. The essence of MCI is that the individual’s cognitive functioning is worse than expected but not bad enough to be classified as dementia. MCI is more challenging to diagnose than dementia because it must be distinguished not only from dementia, at the upper end of severity, but also from normal cognition, at the lower end of severity.

To further confound things, people are not accurate at assessing their own memory or cognitive function, and subjective complaints often do not correlate with objective deficits. Many of those experiencing true cognitive decline often feel they are not, while many who are not experiencing decline often feel they are.

The ability to perform simple math problems, as when handling financial matters, is typically one of the first skills to decline in diseases of the mind, like Alzheimer’s and other forms of dementia. But you may be surprised to learn that even cognitively normal people may reach a point where financial decision-making becomes more challenging.

Why is it that some older people seem to be “as sharp as ever?”

Are they really, or are cognitive problems just not easy to detect? You may know elderly radiologists who still drive, make investment and healthcare decisions, and read CT scans – only to receive a diagnosis of dementia. How can this be? The answer lies in the ability of the brain to compensate for mild cognitive loss, and a person’s ability to adapt to their environment.

A person’s financial decision-making ability peaks in their 50’s, when they have substantial amounts of experience and only modest declines in ability to solve new problems.

The brain’s compensation is related to two kinds of intelligence:

- Fluid intelligence is the ability to solve new problems. It slowly declines over time, starting as early as age 20.

- This is partly offset by our growing experiences and wisdom, known as crystallized intelligence. This type of intelligence tends to plateau in a person’s 70’s, the time at which people become most vulnerable, particularly as they reach their 80’s and 90’s.

Note: A person’s financial decision-making ability peaks in their 50’s, when they have substantial amounts of experience and only modest declines in ability to solve new problems.

Older people adapt to their environment by developing habits and following familiar routines. Such tactics require fewer cognitive demands. Alarms can be used as reminders to take pills or attend appointments. Rooms, such as offices and kitchens, can be organized so that items are always in the same place. Driving can be limited to familiar routes.

The signs of decline can be subtle:

- Focusing on investment benefits and downplaying the risks

- Taking longer to pay bills (especially writing checks that need to be mailed)

- Difficulty with math calculations that become prone to error (e.g., calculating a 15% tip)

- Difficulty understanding concepts like deductibles, minimum balances, inflation, and interest rates

It isn’t all about memory loss

Although you might be or become a “super ager” (individual in their 80’s or beyond who functions at a much younger intellectual level), the vast majority of adults will experience at least some isolated cognitive decline associated with typical brain aging as they progress through their 60’s, 70’s, 80’s and beyond.

Aging has become more or less synonymous with memory loss. Although memory does decline with age, many older people experience far more dramatic declines in non-memory-related cognitive abilities, such as difficulties with concentration, problem solving, and decision-making. Whereas memory loss is a temporal lobe phenomenon, these other abilities are closely linked to deterioration of the prefrontal cortex.

Complex decision-making, such as purchasing financial products and making related decisions, if often the first cognitive function to decline in older adults.

Abnormalities in the brain areas involved in emotion and decision-making, rather than memory, may make some older adults especially susceptible to poor decision-making. Other areas that often change with age include diminished processing speed or quickness of thought; a reduction in the volume of information a person can think about simultaneously (also known as working memory capacity); and slower rate of new learning ability. Complex decision-making, such as purchasing financial products and making related decisions, if often the first cognitive function to decline in older adults.

Factors that influence the aging brain

Cognitive change in older adults is uneven and dependent on many factors, some that may not be intuitive. They include:

- Educational background

- Overall intellectual capacity

- Uncontrolled physical health conditions (high blood pressure, high cholesterol, diabetes, cardiac disease, endocrine dysfunction, autoimmune disorders, pulmonary dysfunction)

- Lifestyle habits (smoking, excessive alcohol consumption, lack of exercise, social isolation, limited intellectual stimulation)

- Mental health conditions (depression, anxiety)

- Mild cognitive impairment (impairment beyond normal cognitive change associated with healthy aging, but not as severe as dementia)

While people with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) may appear relatively intact and function reasonably well in most areas of life, their subtle cognitive deficits put them at even higher risk for poor decision making and financial exploitation.

Elder fraud and financial exploitation – the “Crime of the 21st Century”

Fraud (typically perpetrated by strangers) and financial exploitation (committed by people who occupy positions of trust, such as friends and relatives) are crimes that target older adults. One in five Americans aged 65 or older have been victimized by financial fraud. $3B is taken from seniors per year and only 1 in 44 cases is reported to authorities. Radiologists and other physicians are not immune.

Having adult children who manage an elder’s money decreases the risk of fraud because they prevent strangers from accessing their loved one’s accounts. However, the presence of adult children may increase opportunities for financial exploitation. Despite the common image of stranger scams and paid caregiver thefts, the perpetrators of exploitation are more often family members or trusted friends. Radiologists are not immune.

Where there is a history of family conflict, where an adult child feels he or she is “entitled” to their parent’s money, or where the adult family member is reliant upon the vulnerable adult for basic needs, the potential for financial exploitation increases exponentially.

Social isolation is not only a potential risk factor for financial victimization, it is also a tactic perpetrators use to manipulate their victims and hide acts of exploitation. Fraudsters and financial exploiters use undue influence to limit and control an older person’s social interactions, creating a sense of powerlessness and dependency. This makes elders easier to manipulate, even if they are mentally competent.

Why are the elderly targeted by scammers?

Answers:

- The elderly have a diminished capacity to recognize fraud

- Our nation’s wealth is disproportionately held by older adults

Note: Adults over the age of 65 hold about a third of the nation’s wealth.

Even the most financially literate person can become financially vulnerable, owing to loneliness due to loss of a spouse, physical dependency, or cognitive decline. I repeat: Financial decision-making is often one of the first functions to decline with age. The most preyed-upon age range is 80 to 89.

Financial exploitation victims experience mental health consequences such as shame, depression, and anxiety. In some cases, even suicide.

Common abuses

One of the ways we can protect ourselves and others from fraud and abuse is to be aware of the common crimes being committed. They include:

- Affinity fraud (claiming to be from the same ethnic, religious, career, or community-based group)

- Suddenly-appearing needy “grandkids” of no relation

- Tech support scams (promising to “fix” computers)

- Home improvement scams (scammers take money and don’t do the work)

- Free lunch seminars aimed at recruiting investors

- Free trips

- Lottery scams (false claims of “you’ve won!”)

- Internal Revenue Service (IRS) “agents” offering to settle “back taxes” by pre-paid debit cards

- Fake charities

- Deed theft and foreclosure rescue

- Identity theft

- Credit card fraud

- Fake “official” snail or email (appearing to be from a legitimate bank or business)

- Health care fraud (scammers pretending to be from Medicare)

- Funeral and cemetery scams

Tips to combat loss of financial capacity

- Assemble a “protective tribe” of trusted people who are willing to assist when needed

- Select more than one person to make financial decisions on your behalf, preventing one person from having unbridled access and control over financial assets

- Simplify your financial life (e.g., limit assets to a few mutual funds at one institution, carry no debt)

- Organize important documents in a safe, easily accessible place (bank and brokerage account information, mortgage and credit information, insurance policies, pension/other retirement benefit summaries, social security payment information, contact information for financial and medical professionals)

- Consider a “letter of diminishing capacity”, which authorizes a financial professional to contact a named individual when there is a concern for declining cognitive skills

- Consider creating a durable financial power of attorney

- Keep things up to date (new accounts, trusted contacts)

- Speak up if you think you or someone you know is being taken advantage of

- Have an open conversation with loved ones about investments and other financial matters sooner rather than later

One factor that appears to be linked to better financial decision making in old age is financial literacy. In fact, neuroimaging shows that financial literacy is associated with greater structural and functional connectivity between important brain regions, even after considering the effects of cognitive ability. This is encouraging because financial literacy (defined as “the ability to understand, access, and utilize information in ways that contribute to optimal financial outcomes”) is an ability that could be improved at any age and is therefore a potentially modifiable protective factor against financial exploitation in old age.

Your role as a durable power of attorney

With the rapid expansion of the 65-and-older population comes an increase in the need for legal safeguards for that population. You might be asked to play a role as a durable power of attorney, meaning you agree to manage money or property for someone else (called a principal). In this role, you are a fiduciary, which involves 4 basic duties.

Duties of a fiduciary:

- Act in the principal’s best interest

- Manage the principal’s money and property carefully

- Keep the principal’s money and property separate from yours

- Keep good records

Accepting the role as a fiduciary is a serious decision, with ramifications for both you and the person for whose money and property you agree to manage. What can go wrong? A lot.

Family members might not all agree on important financial decisions. The conflict that results can lead to deep and permanent rifts among family members. This is best addressed with advanced planning. Let’s say you agree to be a fiduciary for your elderly mother. You can have a conversation with her about what she wants before she needs you to make decisions for her. If this isn’t possible, the next best course of action is to look at her past decisions, actions, and statements to determine what she would have wanted.

As a fiduciary, you must avoid all conflicts of interest or even the appearance of a conflict of interest. You can’t make decisions about money or property that benefit you or someone else at the expense of your mother. Generally, this means not borrowing, loaning, or giving her money to someone else unless you know it is in line with what she wants.

Having your son repair your mother’s roof, even if he does that work for a living, may be considered a conflict of interest if you pay him for it with your mother’s money. If you pay yourself, the fee must be reasonable and you should only do so if the power of attorney document or state allows it.

As a fiduciary, you need to be aware of the common signs of financial exploitation. Why? Because your mother may still control some of her funds and can be exploited (and even if she doesn’t control her funds, she can still be exploited). Your mother may have been exploited already and you may be able to intervene. People may try to take advantage of you as the fiduciary. Knowing what to look for will help you avoid doing things you shouldn’t do, protecting you from claims that you yourself have exploited your mother.

Common signs of financial exploitation

- You think money or property is missing

- Your mother tells you money or property is missing

- You notice a change in your mother’s behavior (withdraws large sums of money, tries to wire large amounts of money, uses the ATM a lot, is not able to pay bills that are usually paid, buys things or services that don’t seem necessary, puts names on bank or other accounts that you don’t recognize or that she won’t explain, makes gifts to “new best friends”, changes beneficiaries of a will/life insurance/retirement funds, has a caregiver or other person who suddenly begins handling her money)

- Your mother says she is afraid or seems afraid of a relative, caregiver, or friend

- A relative, caregiver, friend, or someone else keeps your mother from having visitors or phone calls, doesn’t let her speak for herself, or seems to be controlling her decisions

What to do if someone has been exploited

- Call local adult protective services (www.eldercare.acl.gov)

- Alert the bank or credit card company

- Call the local prosecutor or state attorney general

- Call the long-term care ombudsman program or the state Medicaid fraud control unit (if your mother is in a nursing home or assisted living)

- Consider talking to a lawyer

That was a lot to absorb so let me sum it up for you.

- The number of people in the U.S. age 65 and older is increasing faster than any other age group.

- They own ⅓ of the nation’s wealth.

- “Normal aging” involves a loss of fluid cognitive abilities.

- Even cognitively normal people may reach a point where financial decision-making becomes more challenging.

- In other words, cognitively intact older adults may become financially vulnerable.

- Financial decision-making is often one of the first functions to decline with age.

- People are not accurate at assessing their own memory or cognitive function.

- The signs of cognitive decline are often subtle.

- One in five Americans aged 65 or older have been victimized by financial fraud.

- The elderly have a diminished capacity to recognize fraud.

- Radiologists are not immune to any of the above.

If that’s not a sobering stew of facts I don’t know what is!

Our brain partially compensates for certain cognitive losses and we can combat the effects of those losses further by adapting to our environment so that items are easy to locate and common tasks are repetitive and familiar. We can limit the risk of fraud and abuse by being aware of the common crimes being committed and recognizing the signs of exploitation.

We can simplify our financial affairs, organize our financial documents, and make plans for people to manage our finances for us when we’re not able to do it ourselves. (If you agree to be that person, you will be required to be a fiduciary and abide by the legal requirements that are entailed.)

Final note

A person’s protection from financial fraud or exploitation is only as strong as their own financial capacity or that of the person/s who have been granted legal control over their financial decision-making. It doesn’t matter how well you’ve managed your finances over your lifetime if, when you become unable to continue doing so, the person you direct to do it for you is not capable or trustworthy. It’s a sad fact that senior abuse is often committed by a close relative or trusted professional.